My Love-Hate Relationship with Merch

Merch satisfies a very American urge to put one’s interests, opinions, and tastes on display — despite its huge environmental footprint.

By Terry Nguyen

In high school, I worked as a receptionist at a screen printing shop, answering emails and phone calls about customized apparel orders. I left the job after a few months, but I had come to two realizations during this brief stint. The first: Graphic design was not my passion. And the second: People — regardless of age, race, gender, occupation, or political affiliation — love to find a reason to slap a logo, slogan, or image onto any item of clothing, and so long as that design is customized to their tastes, are willing to pay good money for you to bring that vision to life.

These days, making a customizable T-shirt is almost as easy as ordering anything off Amazon. There’s an entire cottage industry devoted to merchandise-making, although brick-and-mortar shops (like the one I had worked for) have been struggling for years to compete against print-on-demand services like CustomInk and RedBubble. It’s a significant source of income for virtual sellers on Etsy and Shopify, whose shops typically offer merchandise geared towards a certain theme, affinity, or ideology, from the innocuous (bachelorette-themed apparel, Harry Potter gear) to the conspiratorial (insurrection shirts for storming the Capitol).

The nature of such merchandise can seem arbitrary, but it reflects a very American urge to put one’s interests, opinions, or tastes on display. The overturning of Roe v. Wade, for example, led to increased demand for pro-choice merch; countless fashion brands pledged to donate proceeds from these items to reproductive rights organizations. Consumerism, after all, is as American as cherry pie, and merchandise is the perfect encapsulation of the First Amendment right to free expression. You don’t even need a good reason to indulge in it. Buyers and sellers alike seem to abide by the universal maxim: You can never have too much merch.

There’s a scene in Baz Luhrmann’s whirlwind of an Elvis biopic where Elvis’s devious manager crafts both “I love Elvis” and “I hate Elvis” pins, so that no matter your opinion on the King of Rock, he could earn a profit from fans and haters alike. It’s an ingenious idea that prevails today. Every celebrity, company, brand, musician, and influencer seems to be hawking some kind of merch, sometimes at high costs. It’s an expected cash-grab for anyone with a solid fanbase (or hater-base).

As someone who primarily shops secondhand, I have a complicated relationship with the merch boom. I love how it’s a sartorial decision that concisely conveys one’s personality and tastes, but I worry about its greater environmental impact. For sellers, it’s challenging to find sustainably-made apparel to print on that doesn’t break the bank. For consumers, the line between what’s sustainable and what isn’t can be quite murky to discern. Rather than assessing clothes on a binary of sustainable vs. unsustainable, I’ve begun to consider its environmental footprint on a spectrum: What type of cotton is used for this merch? (Recycled is typically best.) Is the company taking capping off production once a set amount is sold? Pre-orders or order caps are good indicators that a retailer is mindful of excess stock. Who is profiting from my purchase? Ideally, an independent brand or artist. Will this item still be significant to me in a few years, and will I regret not buying it?

Ethical considerations aside, merch can be fun, bold, ironic, sincere, propagandistic, and even cringe. This depends, of course, on how different people interpret merch. One of my favorite Instagram accounts, @goodshirts, is solely devoted to showcasing and selling graphic tees with nonsensical sayings. The feed is pure absurdity, a haphazard reflection of the global supply chain that powers the international merch landscape. An endless stream of silly slogans, remixed and rehashed onto shirts. It’s bleakly comforting and captures the post-ironic humor of the internet. Shirts (and merch, more broadly) should make us laugh. We already ascribe so much sentiment to it.

There’s also a gratifying sense of exclusivity in donning a T-shirt recognized as cool by a select group of people, akin to being part of a secret club that is in-the-know of a specific artist or brand. It’s conspicuous consumption 101: the practice of purchasing specific goods with the intention to signal one’s status, wealth, or tastes to others. When the phrase “conspicuous consumption” was first coined in the 19th century by sociologist Thorstein Veblen, only the elite class was capable of purchasing luxury items. The proliferation of merch has, for better or for worse, democratized consumers’ ability to put their taste and values on display. Even by moving to a different neighborhood in Brooklyn, where the residents skew younger and wealthier, I’ve noticed a change in the type of merch people sport. I’ve seen more wearers of MadHappy merch, a mental health startup that purports to “create products and experiences to make the world a more optimistic place,” lots of band tees, and upscale athleisure. It’s a departure from the sports tees and jerseys more commonly found on NYC streets, and it reflects not just a demographic shift, but also a cultural one.

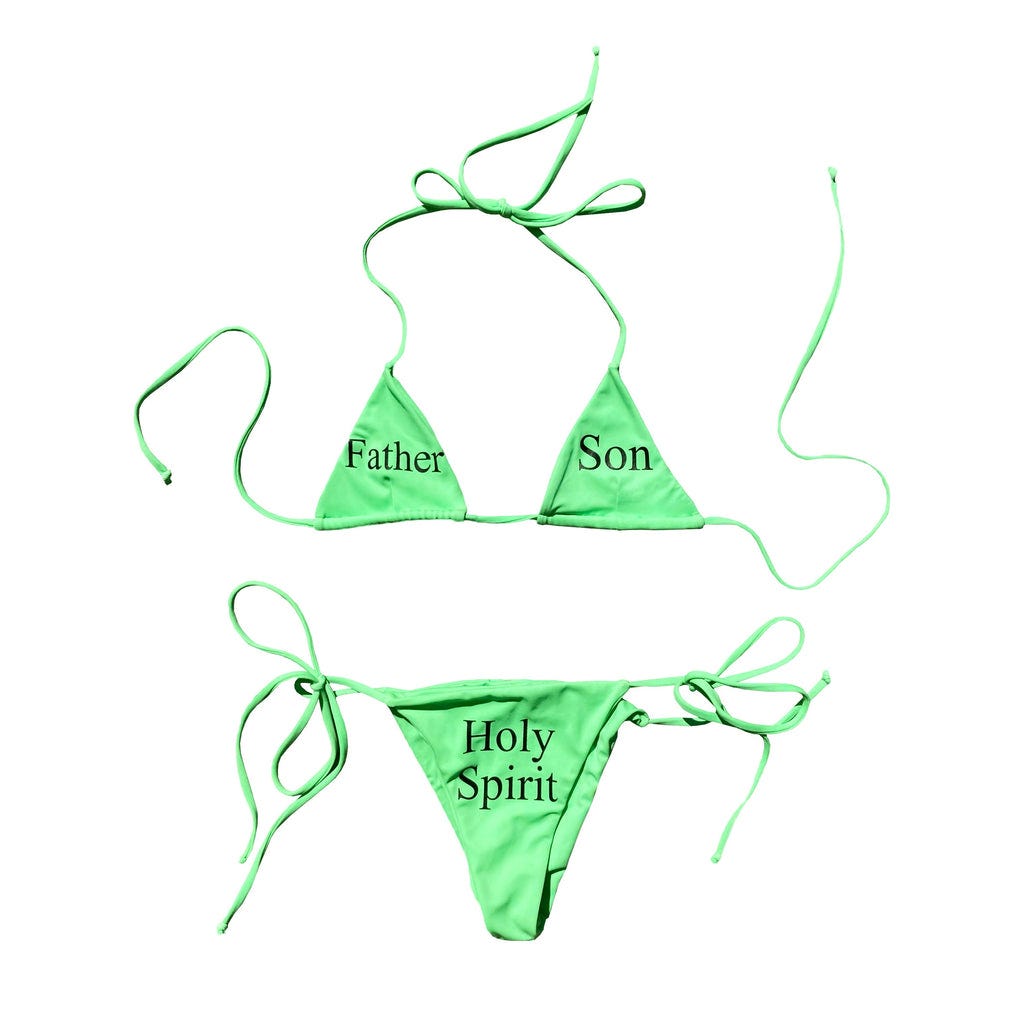

I don’t consider myself a “conspicuous” merch enthusiast with a closet full of graphic tees and branded dad caps. In fact, I’m a reluctant buyer. Most of what I encounter in the wild is poorly made, overpriced, or for lack of a better word, basic. Still, while I’ve suppressed most of my shopping instincts, I’m still easily swayed by cheeky catchphrases and eye-catching designs. I’ve been tempted to buy the Holy Trinity bikini from Praying, a downtown New York fashion brand that sells minimalist merch with phrases, like “Main Character,” “God’s Favorite,” and “Trophy Wife” (the bikini was plain, aside from the printed phrase: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit). I’ve also been quietly pining for a garment from Soulvenir, a Vietnamese brand that sells cool, culturally-specific tees and sweatshirts.

As critical as I am of the merch industrial complex, I believe we have the closet (and brain) space to celebrate well-crafted, creatively designed garments that are fun, expressive, and don't take the world too seriously. It’s better, of course, when merch purveyors are conscious of their environmental impact and consumers are buying with intent.

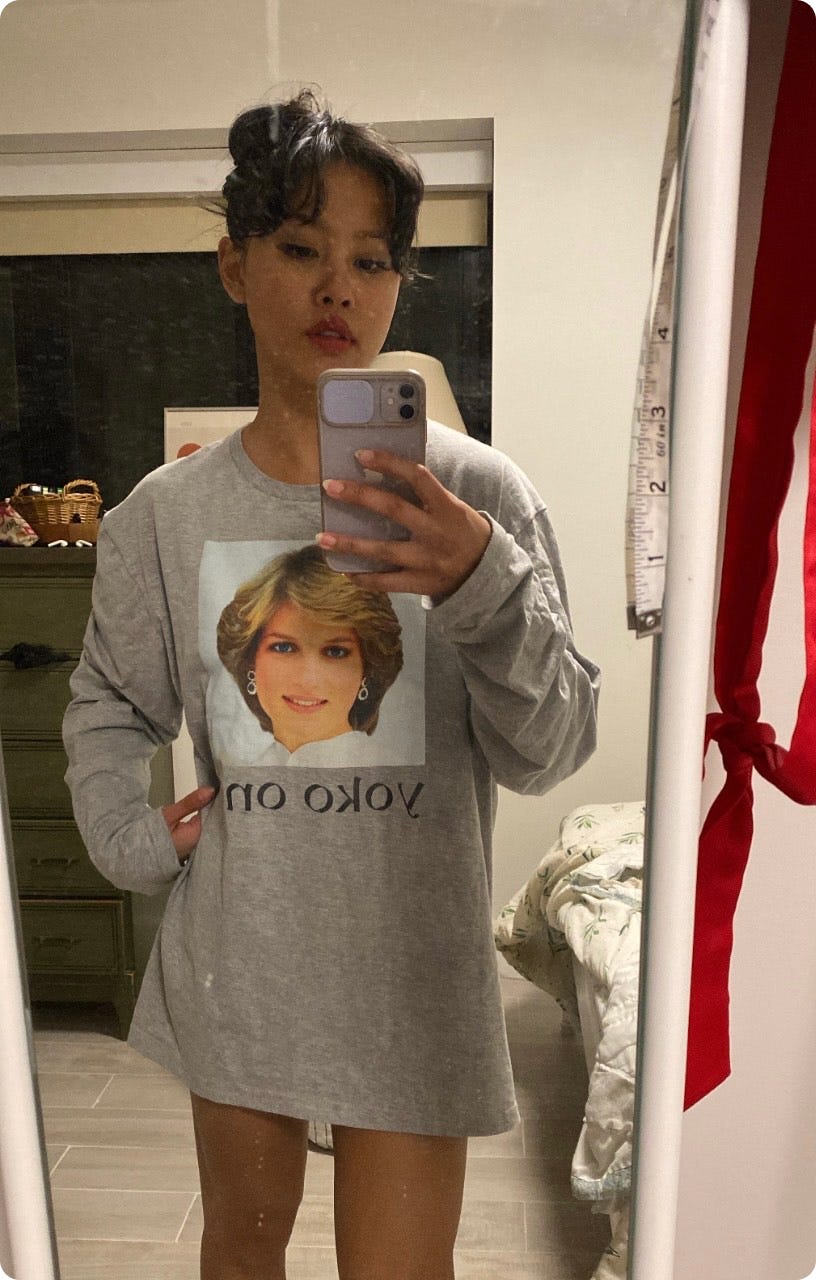

The reality, though, is that sometimes a good shirt isn’t sustainably made. Once it’s in your hands, the best thing you can do is to make it worth its impact: by wearing or upcycling the item, rather than throwing it away. The best shirt I own is from writer Brad Phillips’s Threadless merch shop and was gifted to me. It is an oversized long-sleeve with a cutout of Princess Diana’s face printed above the words “Yoko Ono,” and claims to be “ethically sourced.” The shirt means nothing and everything to me. I only wear it to bed. That, to me, is the beauty of merch. A meaningless statement in a hyper-consumerist world desperate to attribute meaning to everything.

Terry Nguyen is a reporter covering the intersection of culture, technology, and consumerism. She is the senior writer for Dirt, a daily newsletter about entertainment (currently on Substack), and was previously a staff writer for The Goods at Vox.